Monday, March 28, 2022

Not by name

Thursday, March 17, 2022

Tea and sparrows

I went after Buddhism partly because of passages in Thoreau and Emerson, first read in 1963, I think; and they were the same passages that led me to seek out alone time:

I have a great deal of company in my house; especially in the morning, when nobody calls. Let me suggest a few comparisons, that some one may convey an idea of my situation. I am no more lonely than the loon in the pond that laughs so loud, or than Walden Pond itself. What company has that lonely lake, I pray? .... I am no more lonely than a single mullein or dandelion in a pasture, or a bean leaf, or sorrel, or a horse-fly, or a bumble-bee. I am no more lonely than the Mill Brook, or a weathercock, or the northstar, or the south wind, or an April shower, or a January thaw, or the first spider in a new house. -- Thoreau, Walden, "Solitude"

When alone, I have often felt as Thoreau or Emerson did -- that what was to be noticed

was that the dandelion or mullein is not separate but a localized

manifestation of the undifferentiated; the inspection of one's

surroundings yields not things but a unitary happening.

I had a sense the daffodils and fir cones in my surroundings were not burdened by the prescriptive religion I was being taught. Their amorality is not all "make love not war:" watching a preying mantis at work can give one a lot to reflect on. Yet the basic Transcendentalist exercise of "I am this and this is me" coincided with the one enduring maxim I derived from what I was being taught in churches: "do unto others as you would have them do unto you." I could generalize from my desire not to be punched, bitten, or stung. There's a disconnect here between the mantis' ethics and my own, but I'm working to solve that.

I, a presumably hardened skeptic, have admittedly skipped ahead to the golden rule from the moment of unity with all beings, taking the notion that they are somehow connected on ... faith. It comes from sitting still and studying that unity. Immersed in such study, I'm less likely to lash out, and the inner state that goes with not lashing out just feels right.

Buddhism struck me as a sound approach to not lashing out. It had both the unitary vision and simple, powerful ethics which were asserted to arise from that vision. I was, sometimes, put off by the verbosity, though, and approached the literature with some reductionism. I mean, how do you put lightning in a bottle? Even if the bottle is called Buddhism, which comes close to being the name for "the bottle for keeping lightning in that cannot be kept in a bottle."

I came to feel that the Four Noble Truths were but a wordy way to say "do no harm;" the Eightfold Path's recommendations were but a wordy way to say "do no harm;" the Six Paramitas were but a wordy way to say "do no harm;" and all the sutras, etc. were but an especially wordy way to say "do no harm."

I felt I could personally do least harm by setting myself quietly aside from the stream of humanity; and found ways to do that; living alone for years in Atlanta, or in a housetruck hidden in the Oregon woods whenever I could take a break from tree planting; or in a quad near my campus job when I, a householder, ran away from home and family to have my mid-life crisis -- but that last interlude was indeed harmful.

We do some harm when we go for a walk. Multitudes of invisible (to us) lives are crushed underfoot as we go, whether alone or with others. I might not be a preying mantis but in my clumsiness the end is much the same. So really the stricture might better be worded: do less harm. As if that were really possible; yet I think most of us feel this is a reasonable thing to at least try to do.

To go to a zendo and sit is to sit with others, but it is also emphatically to sit alone, "eyes level and nose vertical," as Dogen says, settling deeper and deeper into the solitude that gives each of us the chance to notice we are not separate from one another -- two or twelve or fifty breaths being inhaled, exhaled together in a space set aside for the purpose.

The instructions for this activity vary, but Dogen, cribbing his from a document now over a thousand years old, summarizes it so:

At the site of your regular sitting, spread out thick matting and place a cushion above it. Sit either in the full-lotus or half-lotus position. In the full-lotus position, you first place your right foot on your left thigh and your left foot on your right thigh. In the half-lotus, you simply press your left foot against your right thigh. You should have your robes and belt loosely bound and arranged in order. Then place your right hand on your left leg and your left palm (facing upwards) on your right palm, thumb-tips touching. Thus sit upright in correct bodily posture, neither inclining to the left nor to the right, neither leaning forward nor backward. Be sure your ears are on a plane with your shoulders and your nose in line with your navel. Place your tongue against the front roof of your mouth, with teeth and lips both shut. Your eyes should always remain open, and you should breathe gently through your nose. -- Fukanzazengi

Those of us with arthritis, perhaps, or Tourette's or paraplegia, will immediately see the problem here. Group zazen, held to this or even a somewhat relaxed version of this standard, is profoundly ableist.

I was never able to do all of it, and am rapidly approaching the point where I can do almost none of it. But in a hut I can do it in whatever way darn well works for me, which at present is to lean back in a zero gravity chair and sip "yard" tea as I watch the sparrows, returned from wherever, nervously flitting through blackberries in seach of twigs for their nests. The hut is its own full lotus.

Or a bedroom, or dining room, or seat on a train or bus. Or anywhere at all. Do not think that those currently hiding from bombs, or even those dropping those bombs do not, even then and there, have such moments.

This is common to all. That I think such moments should increase while bombings should cease may be my foolish attachment to illusory non-harm, but I'm, for whatever reason, all-in.

Let's hear it for tea and sparrows.

Saturday, March 05, 2022

Into gold

Along with thoughts of quarantine and masking as temporary hermitary, there's the permanent hermitary of difference.

Imagine a bright assigned-male only-child, culled at a very early age by peers due to a tendency toward effeminacy, by means of stoning.

Imagine the same child, due to or at least shortly after this traumatic incident, losing half of her hearing, and then missing reams of school time due to measles, rubella, mumps, chicken pox, flu and what can only be called depression, surrounded by mumbling and diffident or even abusive adults (she wasn't supposed to have been born).

And then, at 56, having tried all her life to be "normal," transitioned, just in time for the beginnings of a slide of civilization toward authoritarian christonationalism and massive indifference toward human rights, in the midst of a historically isolating pandemic. At the same time, an emergent condition marked by seizures ends her driving years, separating her from society even more.

She's a hermit already by default, as are so many.

Every population identifiable by difference from the norm, as defined and elevated to a principle by the herd, is culled by refused services, redlining, "unemployability" -- all the acts of which a majority (or would-be majority) are capable -- up to and including genocide.

Some of one's time might be spent resisting such a tide. This is activism.

Some of the rest of one's time may be spent in recuperation. It's then that one notices the virtues of the hermitary.

I watch birds. The jays trumpet from the tops of the trees, but never

stay in one spot long. They're autocratic in their actions toward the

songbirds, but watch their backs. On branches lower than those of the

jays, one finds the starlings. Prone to traveling in groups, locally

their flight paths are direct and short, with objectives, all business.

They defer to the jays but find and consume everything with gusto. Lower

still, one finds towhees. They wait for the jays and starlings to suss

out the safe and remunerative places, and investigate when the bigger

birds are satiated.

I watch trees. Most, near the hut, are cottonwoods, and they warn me of approaching storms by turning up fluttering silvered leaves. When there is wind, they bend. When there is stillness, they cleverly compete with one another for a glimpse of the sun, but also share food and information through their buried feet.

Cottonwoods love water, and they are clustered near the seasonal creek. I watch the creek, too, but not as often. I'm told it makes lovely music all day and night, but for me it is silent, unless I bring a hearing device, and hearing devices are tiring. When it runs dry I pick blackberries. When it jumps its banks I abandon the hut for a time, marveling at the power of even a modest amount of flooding.

Here, alone, I am all of me -- observant, prudent, fascinated by my surroundings and increasingly aware of my own thoughts and condition.

Hermiting and meditation have a lot in common, and of course hermits are often meditators. They make a kind of wisdom progress, though that's putting it badly. Wisdom does not build or progress, it's simply revealed by the studied and applied omission of distractions. One peels away the unnecessary, and that which was wise but poorly understood remains.

Buddhism teaches this explicitly.

The field of boundless emptiness is what exists from the very beginning. You must purify, cure, grind down, or brush away all the tendencies you have fabricated into apparent habits. Then you can reside in the clear circle of brightness -- Hongzhi, tr. Leighton.

Those excluded from the mainstream by difference often evince discovered, uncovered, revealed wisdom, and thereby can be exemplars to the very society that has excluded them. What has happened to them is still a crime, but at least it can transmute them into gold.

Friday, March 04, 2022

About that pandemic

One place solitude really shines is when there is a pandemic. By breaking the chain of transmission in the most complete way possible, the occupant of the hermitage performs a service.

Indeed one may think of recent lockdowns and the designation of quarantine sites such as hotel rooms as a bloom of something very like hermitages and hermitaries (cell attached to the monastery).

Isolation during a pandemic is not new; Boccaccio's Decameron (1353), for example, depicts a group of young women and men who retire to a country place to escape the plague. The one hundred stories they tell one another to pass the time is their streaming service.

Undoubtedly their motivation to isolate was fear or prudence; but retiring from the presence of others to prevent transmission from oneself to others has been for some time understood to be a public health measure.

Daniel Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year (1722), for example, recounts lockdown procedures:

The Master of every House, as soon as any one in his House complaineth, either of Botch, or Purple, or Swelling in any part of his Body, or falleth otherwise dangerously Sick, without apparent Cause of some other Disease, shall give knowledge thereof to the Examiner of Health, within two Hours after the said Sign shall appear. ... So soon as any Man shall be found by this Examiner, Chirurgeon or Searcher to be sick of the Plague, he shall the same Night be sequestred, in the same House, and in case he be so sequestred, then, though he afterwards die not, the House wherein he sickned, should be shut up for a Month, after the use of the due Preservatives taken by the rest.

During the Great Depression, prefabicated huts, many of them much like my own, were distributed by the federal government to families needing to isolate a family member stricken by tuberculosis.

|

| Source: New Deal of the Day |

In early March of 2020, our household chose to form a pod with our son, but we did not know if any of us had been exposed to the new virus. We determined to isolate from one another for a set number of days; Beloved made meals and slid them to Son past a plastic sheet that divided the house into two parts; I ransacked the pantry and moved into the hut. I already had water, books, musical instruments, electricity, phone, Internet, and a composting potty, so I felt pretty set.

But, as it turned out, I had likely been exposed just before we closed the gate. Within a week I came down with a serious illness: fever, chills,

shortness of breath, endless coughing, and a sense that my left lung was burning with a cold blue fire. I had never experienced anything like it.

Was it Covid? Local medical authorities had assured us it had not yet reached the area.

Testing was unavailable, and given the emergency that was just beginning to hit the local hospitals, I chose to ride it out. It would have been more responsible to do this if I'd had an oximeter with me, but one can't think of everything.

After a day or two, the fever broke, and I coughed on and on, and slept sitting up, for another seven days. Feeling pretty sure I was no longer contagious, I moved back into the house and rejoined the pod. The others showed no symptoms.

Daughter was our "essential worker" during this time (as during so many other times), bringing groceries and toilet paper from town and dispensing endless, if rather distant, cheer.

As she lived alone, and the County Health Department, where she worked, had at her insistence implemented work-from-home, her place, like the hut, became yet another among millions of "hermitages" across the world.

In her house and ours, missing one another, we lay down at night and rose in the morning keenly aware that we knew nothing of what the future might bring.

But we did feel we were doing rightly.

I think making huts widely available would have helped with this disaster; they are a relatively inexpensive solution, and choosing solitude (when able) on behalf of others is not burdensome if one takes a certain view of things.

Thinking of it this way, a respirator is a hermitage of sorts.

While no one lives forever, let us take care in not making one another ill. Things are tough enough as it is.

As a lamp, a cataract, a star in space

an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble

a dream, a cloud, a flash of lightning:

view all created things like this.

-- Diamond Sutra, Red Pine tr.

Thursday, March 03, 2022

Greet them

In autumn the moon,

and in winter the snow, clear, cold.

I'm a summer baby; I love to fill my eyes with ripening crops. But the hut loves winter.

When snow comes, which doesn't happen every year hereabouts, it brings clarity through the starkness of bare trees and brush, and the invention, new each time, of the unstated promise of white space.

There's not much to think about with snow, which is why it draws the attention of meditators.

Being snowed in, in a warm, tiny space, is adventure, but the novelty wears off quickly and then one discovers one's concentration has deepened.

I tell myself: do not expect or look for such quietude, but do make use of the opportunity. Make tea, crack the books, reach for the highlighter.

After snowmelt begins, sounds return -- cars, ducks, chickens. The creek resumes its song. I remind myself not to regret the return of such "distractions" -- they're not distractions, but are themselves.

Flooding often ensues. The hut, its pier blocks undermined, shifts a little downstream. Oh, well, huh?

Do not expect daffodils, but do greet them. When they bow to spring breezes, maybe bow back.

“From whence did you come?” the Bodhisattva inquired.

“From a Bodhimandala (holy place),” Vimalakīrti responded.

Unable to accept his answer, the Bodhisattva repeated his question, whereupon Vimalakīrti said: “Straightforward mind is the Bodhimandala as it is without falsehood.”

-- Kusumoto Bun’yū, Zengo nyūmon, tr. Michael Sōru Ruymar (edited)

Wednesday, March 02, 2022

Mountain kitchen

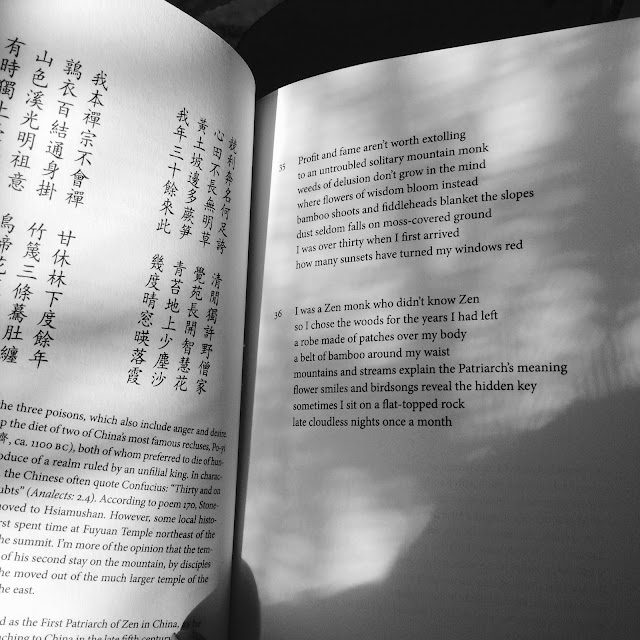

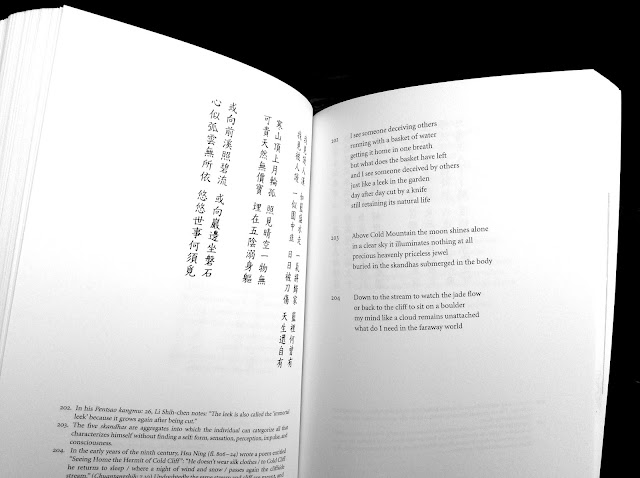

Fourteenth century monk/poet Shiwu (Stonehouse) spent thirty penniless years living in a hut by a spring near a mountaintop in eastern China.

My circumstances are (so far) palatial compared to his, but in the hut I've made an effort to keep things minimalist, as a kind of exercise in privation preparedness.

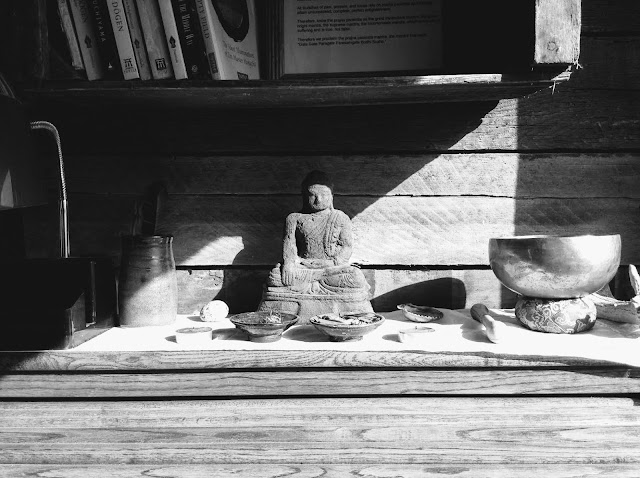

The altar is the focal point of the hut but one's attention is often drawn toward mealtime. Quite a few of Shiwu's Mountain Poems are about food, concerning which he tells us he is not worried, but admits he is certainly preoccupied.

Lunch in my mountain kitchen

there’s a shimmering springwater sauce

a well-cooked stew of preserved bamboo

a fragrant pot of hard-grain rice

blue-cap mushrooms fried in oil

purple-bud ginger vinaigrette

none of them heavenly dishes

but why should I cater to gods

--Tr. Red Pine

I keep a Mason jar filled with rice handy, along with a jar of oatmeal, a jar of cracked mixed grains, and a jar of noodles. There's a salt shaker. And a jar of crushed (almost powdered) vegetable leaf flakes, made from surplus garden foliage which I dehydrate in a homemade solar dryer and then dry-blend. Mason jars are mouse-proof, a consideration in a quiet, isolated hut.

The "veggie powder" can be used in small quantities or large, depending on whether you're thinking of it at the moment as seasoning, trace nutrients, or a substantial part of the meal.

The routine is to put some water in the reservoir of the rice steamer, water and grain and veggie powder and salt in the bowl in the steamer basket, and set the timer. One then does morning service (sometimes this is in the afternoon) and a meal is ready by the time this is over.

I also either have water or tea. Our water comes from a well and I bring it, half a gallon at a time, from the house, as the water in the long garden hose to the hut tends to have algae and micro particles of neoprene in it and so is suspect.

Having read somewhere about using foraged wild or garden foliage for tea (tisane), I have formed the habit of hunting around for what's available on the acre, often gathering enough for the purpose as I go directly from the house to the hut. In season, I may find chicory, dandelions, nipplewort, narrow leaf plantain, crimson clover, deadnettle, cat’s ears, blackberry leaves, fir or spruce needles, money plant, Bigleaf maple flowers, and crop foliage such as kale, chard, beet greens, squash blossoms and leaves, pea and bean foliage, corn silk, and the like.

I layer these into the filter basket of a small four-cup coffee maker, add two cups or more of water, and there's the tea in the carafe in three or four minutes. If I need extra punch, I can add a teabag of black or green tea as needed.

If I've chosen foliage that makes good cooked greens, well, there they are in the filter basket, cooked, and I can add them directly to the rice, cracked grains or noodles. If I prefer soup, I can add the liquid from the carafe to the bowl.

I imagine this, frugal as it is, may be even a more nutritious and varied diet than Shiwu's, and he lived, relatively healthy and spry, into his eighties.

Makes one wonder what a supermarket is for.

Yunyan was boiling some tea. Daowu asked who he was making it for. Yunyan

answered, "nobody special."

-- Soto Zen Ancestors in China, Mitchell, 72

Monday, February 28, 2022

Homework

Over time I have collected some information on eremitic life; a little on Western/Christian traditions, more on Asian, especially looking into Chinese recluse poets and Zen retreatants.

The idea in Asia seems to be to eschew the "red dust" of the cities for several or more years, and then, in most cases, to return to serve society, or at least be open about one's findings to visitors.

One of my favorite reads at the hut is the poetry of Stonehouse, as translated by Red Pine:

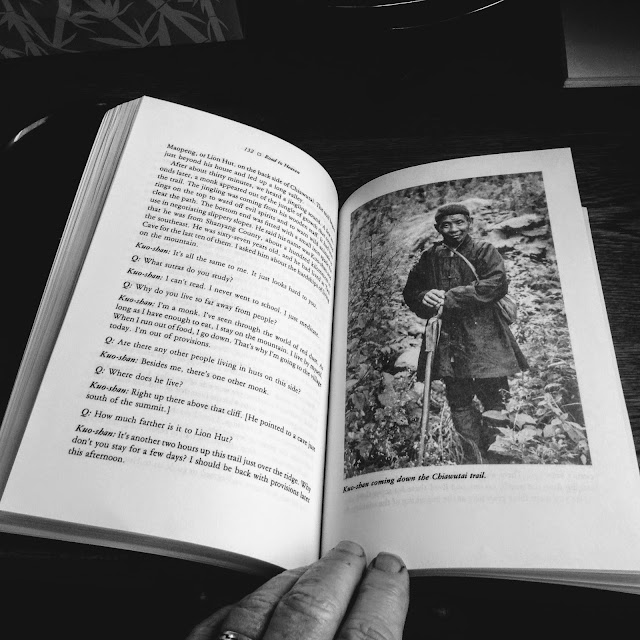

Red Pine's visits to huts and caves in the Zhongnan Mountains produced the standard work in English on contemporary hermits in China.

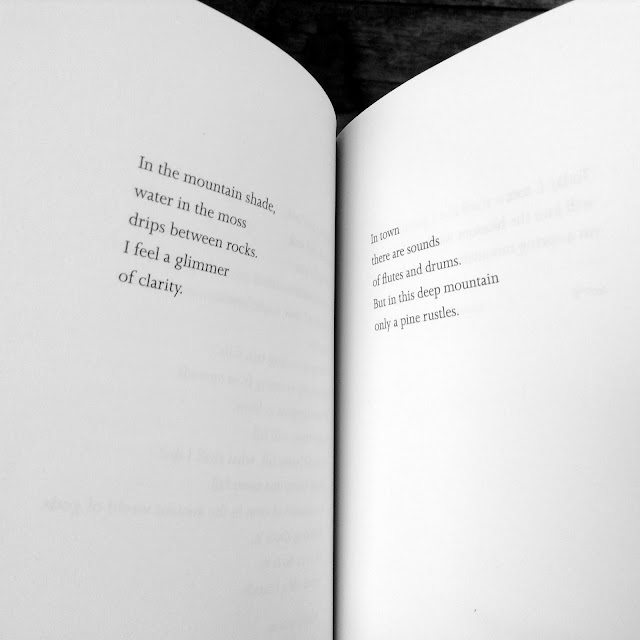

Another favorite is Japanese Soto monk poet Ryokan:

And, of course, Chinese Tang dynasty madman Han Shan (Cold Mountain).

Another text that I return to regularly is Hojo-Ki, "My Ten Foot Square Hut" by Chomei, a Heian poet who retired into the hills near Kyoto.

Ceaselessly the river flows, and yet the water is never the same, while in the still pools the shifting foam gathers and is gone, never staying for a moment. Even so is man and his habitation.

Having moved, as his circumstances were straitened, into smaller and smaller quarters, and having witnessed the destruction of a great many homes during a series of vividly described disasters, he eventually designs for himself a portable (by ox-cart) hut with space for a sleeping mat, tea stove, wash basin, lute, altar, and a few utensils and items of clothing. He professes to be happier there than he has ever been, though his loneliness and misgivings are recounted with wistful honesty.

I know of the lives and thoughts of poet-hermits and Zen master-hermits, because their findings were written down and then, centuries later, translated, and I'm grateful. It does help to follow lamplight when one enters, as it were at night, upon an unfamiliar pathway.

Most of such findings seem to concern the experience of unmediated sensory data -- by which I mean, I look at the shivering leaves of the cottonwoods while not distracted by conversation.

It's like the difference between talking about microbes and having a look through a microscope. I can tell you, to the best of my ability, about what I've seen, later, but I'll say it better if don't step over to you until I've had that solitary look. Does that make sense?

Of course, the hermits in China take a more severe view of the matter than I seem prepared to do. One abbott explained to Bill Porter (Red Pine) that it's necessary for monks to live alone for a long time (years) to rid themselves of their attachment to material things.

Embedded as I am in obligations, and already so dependent in my decrepitude on my zero gravity chair that I might as well be sewn to it, I admit my hut time has been insufficient to clarify my spiritual (if I may call it that) vision. Not enough to be able to make the claim to be able to benefit the world.

But benefit is hard to weigh.

The most I'm going to be able to claim is that down time is a form of restraint. Sitting alone in the middle of nowhere for even an hour, you're not (or mostly not) stealing, lying, murdering, poisoning, misusing libido, abusing substances, backtalking, throwing shade, gossiping, or undermining others. Without going so far as to say these restraints have value, i.e. are beneficial, which, again, is very hard to weigh, we may say that practicing these restraints and clarifying that inward vision seem to bear some relation to each other.

One cannot discover the entire context of an action to determine fully whether or not it is a good or bad one. Be true to yourself and keep your intentions clear of concern for past and future and just do what most appears to be the good thing right now.

Alone, this is easy. Carve a cup and hang it by the spring.

With others, it’s more complicated: Am I offering this cup of water to a friend or an enemy? No way to know! So one just does it.

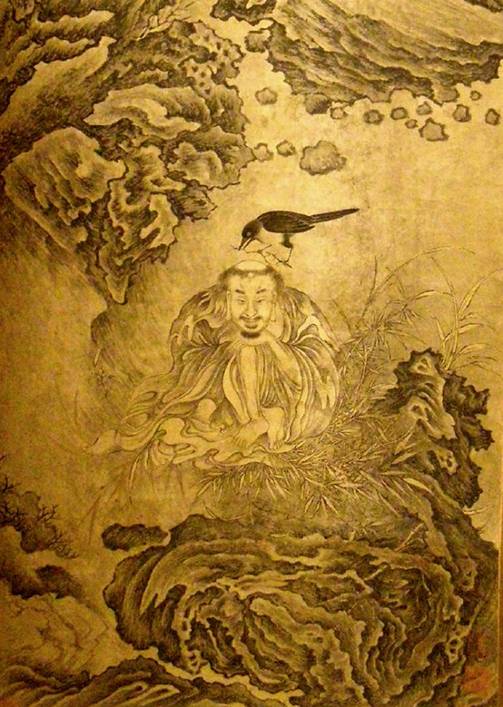

One day, the literary giant Bai Juyi paid a visit to Chan Master Niaoke Daolin. He saw the Chan Master sitting upright by a magpie’s nest, so he said, “Chan Master, living in a tree is too dangerous!”

The Chan Master replied, “Magistrate, it is your situation that is extremely dangerous!”

Bai Juyi heard this and, taking exception, said, “I am an important official in the imperial court. What danger is there?”

The Chan Master said, “The torch is handed from one to another, people follow their own inclinations without end. How can you say it’s not dangerous?” (The meaning is to say that in officialdom, there are rises and falls, and people scheming against one another. Danger is right before your eyes. Bai Juyi seemed to come to some sort of understanding.) Changing the subject, he then asked, “What is the essential teaching of the Dharma?”

The Chan Master replied, “Commit no evil. Do good deeds!” Hearing this, Bai Juyi thought the Chan Master would instruct him with some profound concept. Yet, they were just ordinary words. Feeling very disappointed, he said, “Even a three-year-old child knows this concept!”

The Chan Master said, “Although a three-year-old child can say it, an eighty-year-old man cannot do it.” -- Hsing Yun, Tr. Pey-Rong Lee and Dana Dunlap

So it seems I have homework to do.

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

Investigate this fully

A niece completed her degree at the local university and migrated back to California, so I inherited her card table and matching folding chairs, which I carried out to the hut with ideas of having sangha members over to sit chair zazen with me. Few came, though. Modern visits tend to originate in phone calls and texts, neither of which are part of my universe, so.

The kitchen moved to a crate on the north wall.

For several years the altar rested on a freebie pressboard TV cart.

At almost no cost but my labor, I now had, effectively, a home away from home. Overnighters were few until December 2019, when I elected to live in the hut for an intensive sesshin called Rohatsu.

This consisted of sessions of zazen/kinhin/zazen/kinhin/zazen, thirty minutes of zazen, ten of kinhin, formal meals (oryoki), and semi-formal work-release 😁 (samu), from six in the morning until eight at night, with services featuring chanting of the heart sutra and Fukanzazengi, all carried out in Zoom meetings. There were also formal Skype visits with the teacher, called dokusan.

In between sessions, I mostly drank tea and stared out the windows.

My son tells me what all I'm doing is called "cosplay" and that I'd be better off to just drink tea and stare out the window. 😂

He has a point. I respond that sometimes a framework helps prevent re-inventing the wheel. But I do sound like I'm trying to convince myself of that.

On the other hand, if an inquiry is honest, and I think this one, at its core, is, then I should see where it takes me. One of the things Dogen said to his followers more frequently than just about anything else is "investigate this fully."

Movement isn’t right and stillness is wrong

and cultivating no-thought means confusion instead

the Patriarch didn’t have no-mind in mind

any thought at all means trouble

a hut facing south isn’t so cold

chrysanthemums along a fence perfume the dusk

as soon as a drifting cloud starts to linger

the wind blows it past the vines

-- Shiwu (Stonehouse) tr. Red Pine

Tuesday, February 22, 2022

A level playing field

Then the walls.

And finally even the trim.

In March of 2019 I notified my teacher that my body was beginning to fail me; not only could I not really hear Dharma talks, even with a hearing aid, but I was having trouble lasting through the retreats sitting in a chair, let alone on a kneeling bench.

She advised me to look into practicing with an online sangha. This proved to be a good match, and the hermitage became, in effect, a bit of a monastery, as I began "sitting" with people from all over the planet on a regular basis. The summer heat proved to be no obstacle, as I could simply take my laptop into the house and participate from my relatively cool bedroom.

Spring and fall are the most comfortable times for hut life, but all seasons are good for online fellowship.

Gatherings are important to faiths as a rule, as one gets to practice what one is learning about ethics by interacting with others. Shakyamuni's four truths concern eliminating unnecessary suffering through letting go of regret (past) and anxiety (future), a skill one can practice in a hermitage, but much of the point of having such a skill is to apply it in the presence of others, thus making the means of achieving equanimity available to society at large.

This is why Shakyamuni's fourth truth concerns mostly ethical admonitions. Right speech, actions and livelihood can barely be practiced in a social vacuum. Immersed in a sangha (community of Buddhists), one practices these paths in a setting with agreed-upon rules, then extends the practices into interacting with the wider world.

Since the beginning of the Internet (and even earlier) there have been discussions as to whether teleconference practice "counts," but, in the words of Ikkyu:

A way to lose ourselves in?

An online sangha might seem to present limited opportunity for right action, but by participating in the e-bulletin board, one discovers who needs what and has an opportunity to be of use to them (and, of course, vice versa). All this in a setting in which the action-at-a-distance, non-synchronous nature of online communications importantly provides access for people with disabilities.

I'm nearly deaf, but can hear others through a headset or earbud. I don't see well, but can adjust the distance to the screen, and play with the lighting. I have chronic lumbar strain, but can "sit" in a zero gravity chair. I have memory issues, but can unobtrusively work from an on-screen cheat sheet for all my chanting and ritual needs. I'm incontinent, but can drop out any time by turning off my video, and run to the pottie and back.

Lastly, I'm prone to seizures; if I'm involved in a discussion and feel a petit mal coming, again I can turn off the video for a bit and return when I'm myself again. All this without materially inconveniencing others. Driving to and from our "brick-and-mortar" zendo had taken fifty minutes each way; aside from the carbon footprint, I'd become a bit dangerous and needed to get out from behind the wheel.

Also, as the online sangha records its events, if I'm too sick to log in or am double booked, I can catch up later.

All this was true for not only me but many others, so the online sangha, an almost unique one at the time, provided the one spiritual home many could find, due to a wide array of circumstances and conditions they may have felt could inconvenience others in person.

Laptop hermiting/zazenkai attendance proved to be not only very freeing and provide a level playing field, but perfect for those times the roads were covered with snow or the hut's temperature soared toward a hundred.

And then ... the pandemic arrived.

Sunday, February 20, 2022

Safe to re-occupy

I had been, in a previous life, a chainsaw professional -- but I hadn't been that person in a long time. I sensed, seeing shelf fungi ranging up to the first branches, that this tree's heartwood had been losing cohesiveness for several years, meaning that if I successfully felled it uphill, using a jack, the sapwood could "barber-chair" (split part way up), kick back, and smash the hut anyway.

If I were to take this on, it would have to be done with wire rope, cranked tight, perhaps with a thick hinge, so that the trunk would not separate from the stump as it went down. I hoped also to keep the tree off the fence, less than a foot away from the stump, and off the neighbor's land. This would have to be precise.

Wire rope I had on hand, having dragged it from abandoned clear-cuts in days of yore. Also in the tool shed there were a suitably sized set of single- and double-block pulleys, chains, and a come-along.

I removed all the branches of the tree that I could reach from a ladder placed on the roof of the building, set my "chokers," so to speak, using another large fir tree a hundred feet away as my anchor point. I tightened the cable, working from the anchor end, and then cautiously gnawed away at the tree trunk with a small electric chainsaw, such as is intended for much smaller work.

I distributed my efforts over a period of weeks, much to the amusement of the neighborhood, but eventually the tree began to follow my plan. When at last I was able to take off the remaining branches with a pole saw, it became safe to cut through the hinge and drop the tree trunk.

I cut up the trunk and branches and hauled them away to the woodshed.

Attachment had led, perhaps, to considerable taking of pains, so to speak, but also to a test of patience. What we set out to do, often we find we can, especially if there is no hurry.

While I was working on this project, I noticed that I was not thinking about world problems, or my problems, or in fact much of anything. Hands grasp, arms lift, legs carry. It was as much like meditation as anything I'd ever done that bore the name.

Traditionally in Zen, physical work is practice close to, or on par with, or indistinguishable from, zazen practice. During a sesshin, or days-long zazen-practicing gathering, there are breaks from zazen for chores, called samu. The tradition of labor -- farming, forestry, construction, let alone kitchen and housework -- for monks dates back over a thousand years, and when it's being taught, the story is often told of the Tang dynasty master Baizhang, who, having made such work a rule for his monastery, would not except himself from field labor even in his old age.

“When the master did chores he always was first in the community in taking up work. The people could not bear this so they hid his tools away early once and asked him to rest.

The master said “I have no virtue; how should I make others toil?"

The master having looked all over for his tools without finding them, also neglected to eat.

Therefore there came to be his saying that "a day without working is a day without eating,” which circulated throughout the land.” -- Steven Heine, tr.

When I see a neighbor concentrating on a task, such as ditching with a backhoe or windrowing hay, I feel I'm witnessing something that is not different from zazen, in the sense that in the immediacy of the task, all pretensions, regrets and preconceptions drop away. All zazen has going for it is a deliberate effort to extend that immediacy -- which has the goal of the effortlessness that comes when there is no goal.

Desiring to have a hut in which to drop desire is ironic, of course, but to lift yourself by your bootstaps you begin by having bootstraps. Anyway, the building was now safe to re-occupy.

Do not think “good” or “bad.” Do not judge true or false. Give up the operations of mind, intellect, and consciousness; stop measuring with thoughts, ideas, and views. Have no designs on becoming a buddha. How could that be limited to sitting or lying down? -- Dogen, Fukanzazengi

Friday, February 18, 2022

Making an inhabitable space

As we worked on the playhouse in 1994, near the fence, a neighbor strode purposefully over. I chirped, "Hi! The kids had a playhouse like this at our last place, so we're building a replacement."

"Oh, okay." He pushed his ball cap, with its tractor-supply embroidery, back from his forehead. "I was gonna tell ya th' county don't allow building within ten feet of the th' line."

I had suspected as much, but seeing as we already had a building that close, namely the large stamping shed up in the corner, built in the 1960s, I had hoped the new little shed would not be an issue.

It must not have been, at least as a playhouse, because we never met the man again, other than to wave at him as he roamed around beneath his oak trees on his riding lawnmower.

In 2009, an empty nester and retiree, I looked over the little building, to which I'd paid little interest over the years, and thought it might be a suitable place to read and write. I brought yet more materials -- old carpets for insulation, old fence boards for the interior walls -- and reroofed the building.

For reading, I put in rustic shelves and a comfy chair.

For writing, a small desk and office chair. There was an old metal folding cot that had been my dad's, which I covered with a bit of foam and a blanket. In warm weather I could take breaks by napping on the cot.

The hut was off grid at first, being well away from the house, but

laptop batteries and thermal mugs offer a few hour's independence. As

winter came, I ran power to the hut and added a low-wattage space

heater.

Eight by ten, insulated, with a low ceiling, warms quickly even in winter, and I was able to leave the thermostat on a very low setting, or even turn off the heater and dress in layers.

Once you have power, though, one thing will lead to another. In 2014 it occurred to me to add a rudimentary kitchen.

The centerpiece was a thrift-store steamer that was missing its oblong plastic basket liner. I found that it could make assorted meals perfectly well in a bowl placed in the basket.

One fills the water reservoir, places the bowl under cover (not shown), and sets the timer. In five minutes it made ramen, in twenty it made rice, and even announced lunch with a pleasant "ding" as the mechanical timer wound down.

You might think the only thing missing was a bathroom. I had run a garden hose out to the hut and brought a couple of steel bowls from the house, with towels and the like, for various purposes. As for other business, I could run to the house, but friends had given us a composting potty, and I elected to park it in the barn, halfway between the hut and the garden and so convenient to both.

It was now possible to be independent from the house for days at a time.

Not that there was anything wrong with running to the homestead, and as a rule I hung out more there than at the hut. It has been a fine place to hang out.

The idea I was forming in my mind, though, was to try to spend part of every day, or of every available day, in a concentrated space, with relatively few things and distractions. Would it be possible, in short, at least on Thursdays, to emulate one of my childhood heroes?

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only

the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had

to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I

did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I

wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to

live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and

Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad

swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its

lowest terms ... --Thoreau, Walden