Over time I have collected some information on eremitic life; a little on Western/Christian traditions, more on Asian, especially looking into Chinese recluse poets and Zen retreatants.

The idea in Asia seems to be to eschew the "red dust" of the cities for several or more years, and then, in most cases, to return to serve society, or at least be open about one's findings to visitors.

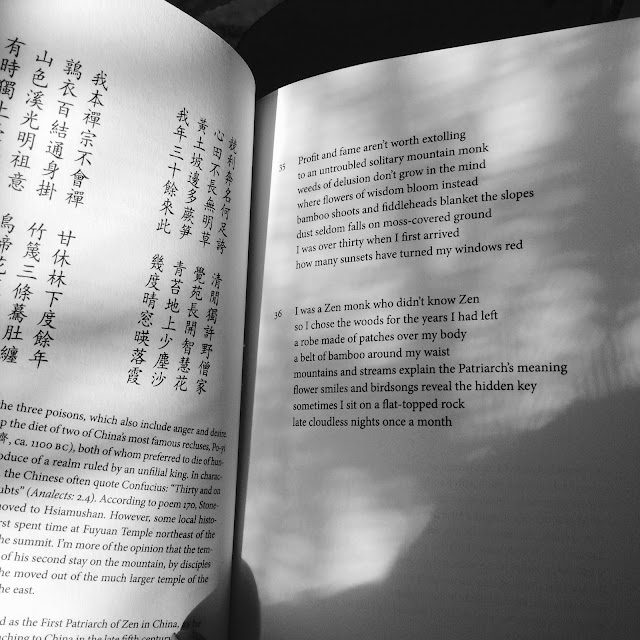

One of my favorite reads at the hut is the poetry of Stonehouse, as translated by Red Pine:

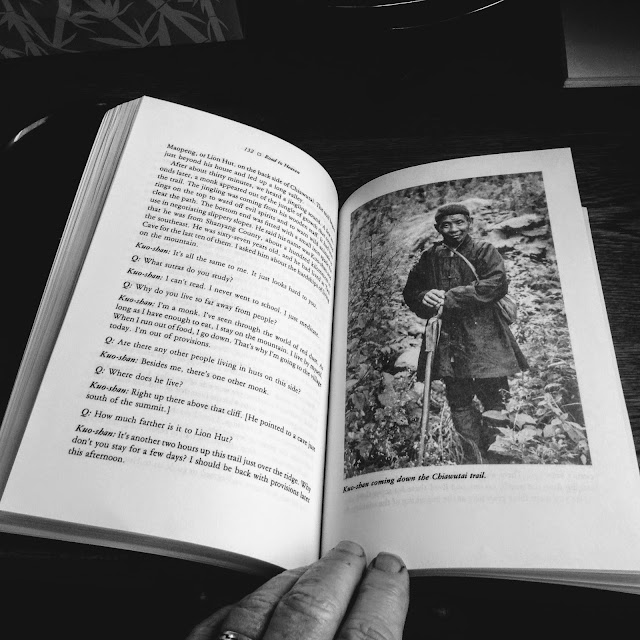

Red Pine's visits to huts and caves in the Zhongnan Mountains produced the standard work in English on contemporary hermits in China.

Another favorite is Japanese Soto monk poet Ryokan:

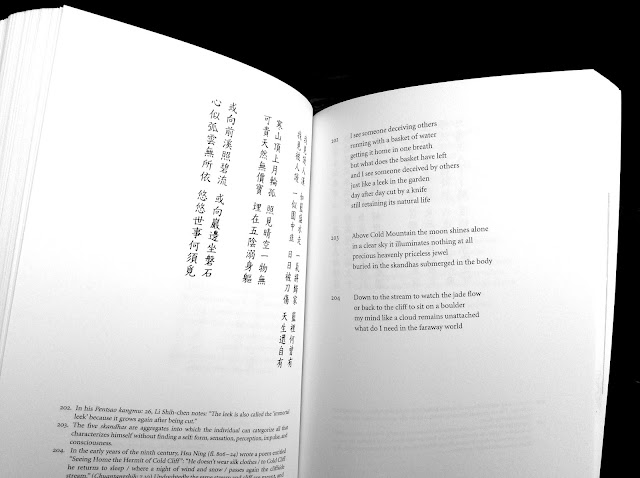

And, of course, Chinese Tang dynasty madman Han Shan (Cold Mountain).

Another text that I return to regularly is Hojo-Ki, "My Ten Foot Square Hut" by Chomei, a Heian poet who retired into the hills near Kyoto.

Ceaselessly the river flows, and yet the water is never the same, while in the still pools the shifting foam gathers and is gone, never staying for a moment. Even so is man and his habitation.

Having moved, as his circumstances were straitened, into smaller and smaller quarters, and having witnessed the destruction of a great many homes during a series of vividly described disasters, he eventually designs for himself a portable (by ox-cart) hut with space for a sleeping mat, tea stove, wash basin, lute, altar, and a few utensils and items of clothing. He professes to be happier there than he has ever been, though his loneliness and misgivings are recounted with wistful honesty.

I know of the lives and thoughts of poet-hermits and Zen master-hermits, because their findings were written down and then, centuries later, translated, and I'm grateful. It does help to follow lamplight when one enters, as it were at night, upon an unfamiliar pathway.

Most of such findings seem to concern the experience of unmediated sensory data -- by which I mean, I look at the shivering leaves of the cottonwoods while not distracted by conversation.

It's like the difference between talking about microbes and having a look through a microscope. I can tell you, to the best of my ability, about what I've seen, later, but I'll say it better if don't step over to you until I've had that solitary look. Does that make sense?

Of course, the hermits in China take a more severe view of the matter than I seem prepared to do. One abbott explained to Bill Porter (Red Pine) that it's necessary for monks to live alone for a long time (years) to rid themselves of their attachment to material things.

Embedded as I am in obligations, and already so dependent in my decrepitude on my zero gravity chair that I might as well be sewn to it, I admit my hut time has been insufficient to clarify my spiritual (if I may call it that) vision. Not enough to be able to make the claim to be able to benefit the world.

But benefit is hard to weigh.

The most I'm going to be able to claim is that down time is a form of restraint. Sitting alone in the middle of nowhere for even an hour, you're not (or mostly not) stealing, lying, murdering, poisoning, misusing libido, abusing substances, backtalking, throwing shade, gossiping, or undermining others. Without going so far as to say these restraints have value, i.e. are beneficial, which, again, is very hard to weigh, we may say that practicing these restraints and clarifying that inward vision seem to bear some relation to each other.

One cannot discover the entire context of an action to determine fully whether or not it is a good or bad one. Be true to yourself and keep your intentions clear of concern for past and future and just do what most appears to be the good thing right now.

Alone, this is easy. Carve a cup and hang it by the spring.

With others, it’s more complicated: Am I offering this cup of water to a friend or an enemy? No way to know! So one just does it.

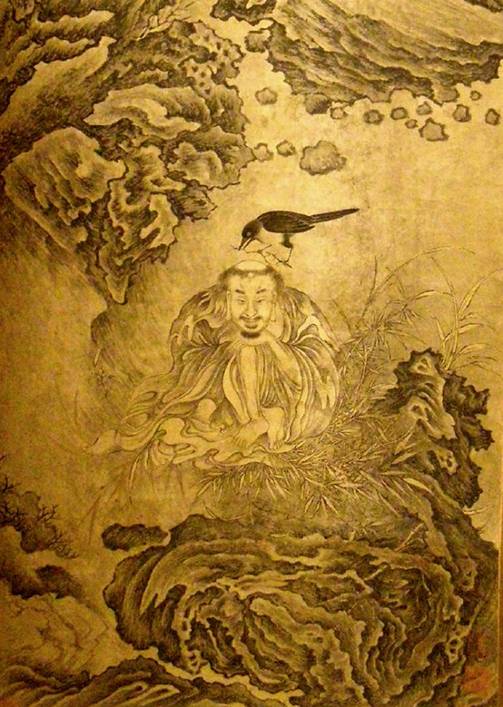

One day, the literary giant Bai Juyi paid a visit to Chan Master Niaoke Daolin. He saw the Chan Master sitting upright by a magpie’s nest, so he said, “Chan Master, living in a tree is too dangerous!”

The Chan Master replied, “Magistrate, it is your situation that is extremely dangerous!”

Bai Juyi heard this and, taking exception, said, “I am an important official in the imperial court. What danger is there?”

The Chan Master said, “The torch is handed from one to another, people follow their own inclinations without end. How can you say it’s not dangerous?” (The meaning is to say that in officialdom, there are rises and falls, and people scheming against one another. Danger is right before your eyes. Bai Juyi seemed to come to some sort of understanding.) Changing the subject, he then asked, “What is the essential teaching of the Dharma?”

The Chan Master replied, “Commit no evil. Do good deeds!” Hearing this, Bai Juyi thought the Chan Master would instruct him with some profound concept. Yet, they were just ordinary words. Feeling very disappointed, he said, “Even a three-year-old child knows this concept!”

The Chan Master said, “Although a three-year-old child can say it, an eighty-year-old man cannot do it.” -- Hsing Yun, Tr. Pey-Rong Lee and Dana Dunlap

So it seems I have homework to do.